Image Credit: Moa by John Megahan, used under CC BY 2.0 / Cropped from original.

Moa, the gigantic, flightless birds that once roamed New Zealand, are an iconic example of extinct megafauna. These birds, belonging to the Dinornithiformes family, have intrigued scientists for years, but much remains unknown about their feeding habits, niche partitioning, and how their extinction affected New Zealand’s ecosystems. This gap in knowledge has implications for understanding how the removal of these birds might have impacted the native biota and the potential for introduced species to take on their ecological roles.

In this study, we used cutting-edge 3D finite-element analysis to examine the skulls of five moa genera and two extant ratites (flightless birds like ostriches and emus) to better understand the biomechanical performance of their skulls and predict their feeding behaviours. This innovative approach provides a clearer picture of how moa species may have used their beaks and skulls to process food, and how their feeding strategies differed from one another and from their living relatives.

Using 3D Technology to Unlock Moa Feeding Behaviours

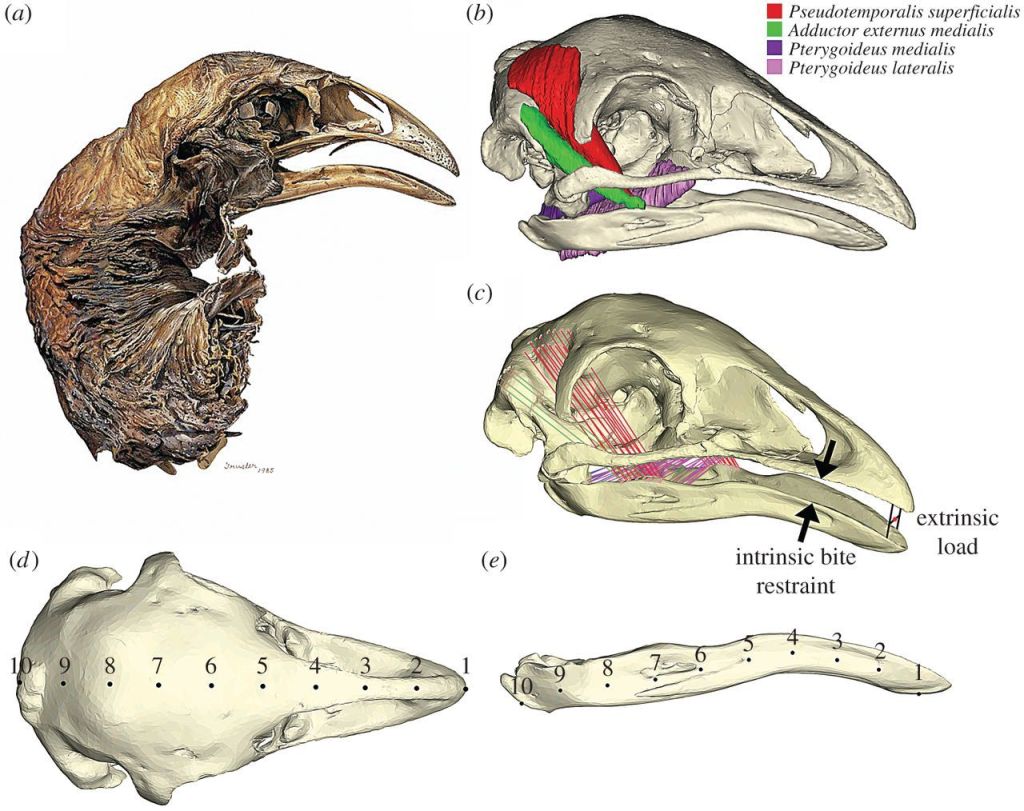

The key to understanding moa feeding strategies lay in the muscles used for jaw movement. To reconstruct this, we used MRI scans of a mummified moa to digitally extract the jaw muscles and pinpoint where these muscles attached to the skull.

With this information, we created detailed 3D models of moa skulls, which allowed us to simulate various feeding behaviours, such as clipping twigs, shaking, and pulling food. We compared the mechanical performance of these models with those of extant ratites, like the emu, to assess how the moa’s skull would have coped with different food acquisition strategies.

Key Findings: Diverse Feeding Habits Among Moa Species

Our research revealed that moa species likely had very different ways of foraging for food. While there was some overlap in biomechanical performance between the emu and the upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus), overall, moa species exhibited a broad range of feeding behaviours. This diversity in skull mechanics suggests that each moa species exploited its environment in unique ways, which may have helped maintain their high levels of diversity in prehistoric New Zealand.

For example, while some moa species might have specialised in clipping tough vegetation with their powerful beaks, others might have used their skulls in different ways to shake or pull food from the environment. These differences in feeding strategies could have been a key factor in the ecological success and diversity of these birds before their extinction.

Von Mises stress contour plots from FEA of ratite crania in dorsal view. The models are subjected to four loading conditions: unilateral clip, pullback, lateral shake and dorsoventral pull. Figure from Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2016. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2015).

Implications for Ecological Understanding

Understanding how moa species fed provides valuable insight into their role in the ecosystem and helps reconstruct the prehistoric environments of New Zealand. The diverse feeding behaviours of moa likely contributed to their success as herbivores, and their extinction left a notable gap in the ecosystem. Our findings also shed light on the challenges of introducing exotic species as potential ecological “surrogates” for the extinct moa, as no single species can truly replicate the complex and varied feeding behaviours of these once-dominant birds.

This study not only improves our understanding of moa biology but also highlights the importance of preserving biodiversity and considering the intricate ecological roles that extinct species once played in their habitats.