Decline and Extinction Threats to Australia’s Marsupial Carnivores

In Tasmania, European settlement brought profound changes to the island’s native carnivores. Historically, Tasmania’s carnivore guild included the iconic thylacine, alongside three dasyurids: the Tasmanian devil, spotted-tailed quoll, and eastern quoll. Thylacines, distributed across the island apart from the southwest, faced rapid population declines. Despite clear signs of their dwindling numbers, protection only arrived in 1936, a mere two months before the last known captive thylacine passed away.

Today, other marsupial carnivores face their own extinction threats. Tasmanian devils, for instance, have suffered dramatic declines, most recently due to a fatal contagious cancer that spread rapidly in the late 1990s. Eastern quolls, now extinct on mainland Australia, have lost up to 90% of their range, and spotted-tailed quolls are only found in small, isolated populations. Studying the extinction drivers of the thylacine offers valuable insights for conserving these remaining species.

Research Aim

The primary goal of my PhD research was to unravel the feeding ecology and extinction risk factors of the thylacine—also known as the Tasmanian tiger—while exploring the ecological resilience of its closest living relatives. This study draws on cutting-edge techniques to clarify the diet and foraging behaviours of these elusive creatures.

Uncovering the Thylacine’s Diet and Feeding Strategies

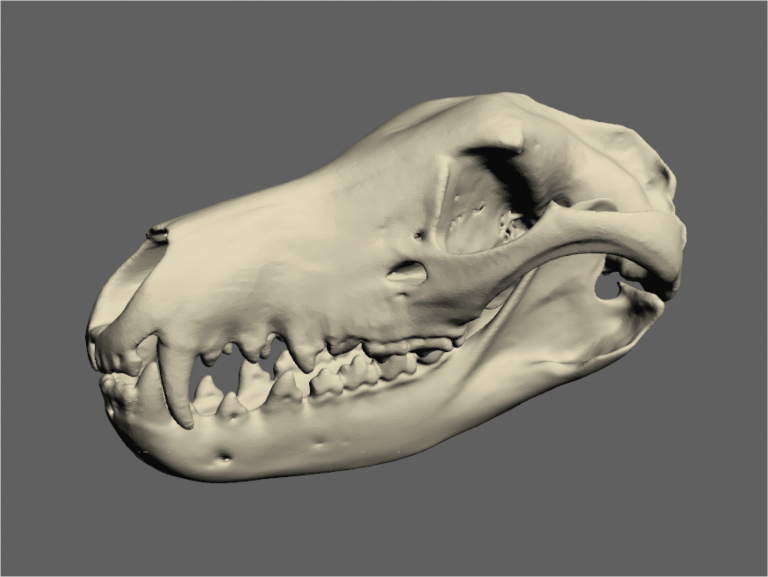

Since the thylacine’s extinction, its diet and feeding behavior have been a source of controversy. Although their dentition suggests a carnivorous diet, specific prey preferences have remained unclear. To shed light on this mystery, I employed two interdisciplinary techniques:

- 3D Skull Biomechanics: Using advanced 3D computer simulations, I compared the thylacine’s skull structure with that of extant marsupial carnivores. This analysis helped determine whether thylacines were specialized hunters of small prey or could tackle larger animals.

- Stable Isotope Analysis: I measured stable isotope ratios of carbon and nitrogen in preserved thylacine tissues, assessing dietary variation over time. For broader ecological context, I also analysed the isotope data from specimens of Tasmanian devils, spotted-tailed quolls, and eastern quolls, spanning from the 1830s to today.

Research Findings

1. Prey Size Limitations Biomechanics analysis indicated that thylacines likely specialised in smaller prey. This limitation may have left them vulnerable to habitat changes and the pressures of European settlement, including intensive hunting and habitat degradation. The dietary specialisation of thylacines could explain why they struggled to adapt to changing landscapes.

2. Prey Composition and Dietary Preferences Through stable isotope analysis, we evaluated the thylacine’s diet composition, identifying key prey types across different individuals. Although publication on these findings is forthcoming, this study has already provided new insights into the ecological niche of this unique marsupial predator.

3. Long-Term Shifts in Marsupial Carnivore Ecology The stable isotope data revealed intriguing shifts in the feeding habits and habitat use of marsupial carnivores over the past 180 years. This trend suggests that these species are highly responsive to environmental changes, which could be a critical factor in their management and conservation. Primary drivers of these shifts may include changes in vegetation and nutrient availability.

Fieldwork and Institutional Support

One of the unforgettable aspects of this research was conducting fieldwork alongside museum curators and fellow scientists. This work was supported by numerous museums and wildlife parks, where we gathered samples and collaborated on data collection.

A particular highlight was conducting whisker growth trials in captive Tasmanian devils to inform our isotope analyses. Thanks to the incredible staff and collaborators across several zoos and parks, we gained vital insights that strengthened our study.

Museums and Institutions that Supported this Research:

- American Museum of Natural History — New York, USA

- Australian Museum — New South Wales, Australia

- Booth Museum of Natural History — Brighton and Hove, UK

- Cambridge University Zoological Museum — Cambridge, UK

- Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum Senckenberg — Frankfurt, Germany

- Gothenburg Museum of Natural History — Gothenburg, Sweden

- Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, University of Glasgow — Glasgow, UK

- Leeds City Museum — Leeds, UK

- Museum Victoria — Victoria, Australia

- Naturhistorisches Museum Wien — Vienna, Austria

- Natural History Museum — Oslo, Norway

- National Museum of Australia — Canberra, Australia

- Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery — Tasmania, Australia

- The Field Museum — Chicago, USA

- Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery — Tasmania, Australia

- Western Australian Museum — Western Australia, Australia

- Westfälisches Landesmuseum mit Planetarium — Münster, Germany

- World Museum Liverpool — Liverpool, UK

- Yorkshire Museums and Gardens — York, UK

- Zoological Institute & Museum of the Ernst Moritz Arndt University — Greifswald, Germany

We received tissue samples from researchers Bronwyn Fancourt at the University of Tasmania, Sarah Peck at the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE), and Damien Stanioch.